In 1787, when asked about his opinion of the Philadelphia constitutional proceedings happening in secret, Patrick Henry famously replied, “I smell a rat!” Henry opposed the proposed Constitution because he feared it would centralize power in a strong national government. This put Henry at odds with the Federalists, who viewed the existing Articles of Confederation as an insufficient yoke to bind the several states into “a more perfect union.” But Henry was not alone in his opposition. Many throughout the newly independent states shared his fears. Collectively, they came to be known as Antifederalists, and New Hampshire had a strong contingent.

In 1787, when asked about his opinion of the Philadelphia constitutional proceedings happening in secret, Patrick Henry famously replied, “I smell a rat!” Henry opposed the proposed Constitution because he feared it would centralize power in a strong national government. This put Henry at odds with the Federalists, who viewed the existing Articles of Confederation as an insufficient yoke to bind the several states into “a more perfect union.” But Henry was not alone in his opposition. Many throughout the newly independent states shared his fears. Collectively, they came to be known as Antifederalists, and New Hampshire had a strong contingent.

According to Jere R. Daniell, writing in New Hampshire: The State that Made Us a Nation, Federalist sympathies were “strongest among the upper classes,” while the working classes, farmers, tradesmen, and the like, were firmly in the Antifederalist camp. Though no pollsters were around to gauge public opinion, it doesn’t seem out of bounds to infer the Antifederalists outnumbered the Federalists. The upper classes typically make up the smallest segment of a population. However, they did have an advantage. They knew how to manipulate legislative rules.

Federalists recognized the weakness of their position, as fierce debates about the Constitution had been occurring since its October 1787 debut in Portsmouth. The pro-centralization forces, however, had an ace in the hole – they “controlled state planning for the upcoming convention” to decide whether New Hampshire would ratify the document. With that, Seacoast resident John Sullivan, who also happened to be President of New Hampshire (Governor), schemed to call a special legislative session in December, rather than wait for the regularly scheduled meeting set for late January. He did this to catch the opposition by surprise and increase the likelihood that Federalists could control the outcome.

And they did. The Federalists were able to set the ratifying convention for February, by which time they hoped Massachusetts and other states would have ratified. They also were able to set aside, for the convention, the state’s exclusion bill. The bill “prohibited state officials from simultaneously representing their towns in the legislature.” By setting it aside, Sullivan’s side allowed “the participation of influential Federalists like Superior Court Chief Justice Samuel Livermore of Grafton County and State Treasurer John Taylor Gilman.”

Having been bested in the special session, Antifederalists worked to bolster their position leading up to the convention. “The plan was simple: elect Antifederalist delegates and bind them by written instructions so they could not … be talked out of voting nay.”

The Federalists became alarmed when they learned of the number of bound delegates who were against ratification, so they devised a new strategy. If they suspected ratification would fail, then they would maneuver to postpone the vote until later in the year.

The convention came and the debates over the Constitution ensued. During the arguments, leaders from both sides tried to ascertain the number of likely yes and no votes. To the Federalists, the outcome did not look promising. Antifederalists had a strong majority, meaning the Constitution would fail if it were brought to a vote. Thus, Sullivan and his cohorts went to their contingency plan and managed to get an adjournment.

Because of the postponement, the convention would not reconvene until June and the Federalists began a media onslaught to sway opinions. Some of the writings were editorials espousing the benefits of the Constitution, but others were nothing more than smear campaigns. The articles gave the impression Antifederalists had been behind a paper money riot in 1786. They also “publicized personal financial problems of [Nathaniel] Peabody and others.”

Antifederalists, meanwhile, focused on trying to maintain the numbers of bound delegates they had garnered before. In the end, as we know, the Federalist tactics succeeded and on June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution, technically bringing the new law of the land into effect. Once Virginia and New York ratified shortly thereafter, the Antifederalists knew their cause was lost.

The rat on the Potomac has swelled to gargantuan proportions, such that even the most ardent Federalists would likely shrink in horror at the specter of its ravenous appetite for power. Courtesans at the altar of government continue to swirl eddies that suck dominion over all things to Washington. Yet, not all stand idly by amidst the centralizing impetus. The Free State Project, and those who share its goals, aim to peaceably slow, nay even reverse, the erosion of liberties that result from the ignoble rat’s ascension. It is a tradition that harks back to the earliest days of a free and independent New Hampshire. For, as Thomas Jefferson said,

“When all government, in little as in great things, shall be drawn to Washington as the Center of all Power, it will render powerless the checks provided of one government on another and will become as venal and oppressive as the government from which we separated.”

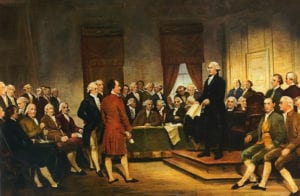

Painting by Junius Brutus Stearns